The unprecedented bushfire crisis that has raged through our country, will change us all forever. Kathryn Kernohan reports.

It will be looked back on as the summer that changed Australia forever. The devastating bushfire season of 2019-20 has had a profound impact on Australian communities, wildlife, infrastructure, our economy and ultimately, our way of life.

The devastating bushfire season of 2019-20 has had a profound impact on Australian communities, wildlife, infrastructure, our economy and ultimately, our way of life. The sheer size, scope and impact of the crisis can only be summed up by the numbers. Since September 2019 when fires began to spark, more than 18.6 million hectares of land have been burned, most significantly in Victoria and New South Wales but also in Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia.

To put the size of the impacted land in context, it is larger than the entire land area of England which is home to around 55 million people (13 million hectares). It’s more than twice the size of Belgium and more than 14 times the size of Japan.

Tragically, the biggest loss has been that of human life. At the time of publishing, 34 people had died as a direct result of the bushfires, the number including people who died trying to defend their properties and a number of paid and voluntary firefighters from both Australia and the US.

A staggering one billion animals are estimated to have perished, a figure that does not include fish, bats or frogs. Experts predict that many more animals will die in coming months as a result of the loss of their habitat and food sources, and also fear that some of Australia’s most loved species including the koala and quokka will be under severe threat when the final toll of the bushfires is known.

Over the summer, most Australians saw footage from bushfire-impacted communities that was difficult to reconcile with what we usually associate an Australian summer with - barbecues, the beach and sport. Footage like that from the small Victorian coastal fishing town of Mallacoota, where residents and holidaymakers huddled together on the beach, wearing facemasks under an apocalyptic orange-black sky. Closed roads as a result of bushfires meant people had to be evacuated to safety by navy ships. In the aftermath of the evacuation, Mallacoota remained isolated from the rest of Victoria for weeks due to the closure of the Princes Highway.

There was also unprecedented and unthinkable destruction to the usually picturesque Kangaroo Island in South Australia, which had been home to 150 species of native Australian wildlife. In January, about half of the island was burned. An estimated 30,000 koalas - roughly half the island’s population - didn’t survive.

Adding to the heartache was the fact that Kangaroo Island’s koalas are free from chlamydia, which greatly impacts wild koala populations in other parts of the country and is the most significant disease-causing death among the species. Kangaroo Island’s koalas had been previously cited by experts as key to saving the species.

As of mid-January, over 10,000 buildings including more than 2,300 homes had also been destroyed around the country. The full extent of the damage is not yet known but it is clear that schools, businesses and other vital infrastructure have been lost.

The currently known and expected impact is so great that US climatologist Michael Mann from Pennsylvania State University told Time magazine that this bushfire season may result in people and communities becoming “climate refugees”. “We’re seeing the beginning stages of monumental, catastrophic climate changes that will ultimately drive people away from large inhabited regions of this continent,” he said.

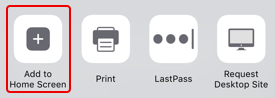

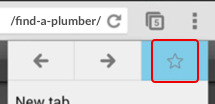

A number of campaigns and initiatives were established early in the year to support people and families who had been displaced by bushfires. One example was find Find A Bed, launched on New Years Eve with the aim of connecting people in need of emergency accommodation with free temporary or longer-term accommodation. In a short period of time, more than 6,500 people across Australia registered to open their properties to assist.

Private drinking water in bushfireaffected areas has also been severely impacted. Dr Brett Sutton, Victoria’s Chief Health Officer, issued a public warning that tank drinking areas in impacted communities where fire retardant and water bombing had occurred could be contaminated with fire retardant, debris, ash or even dead animals.

In towns such as Eden, Boydtown, Cobargo and Bermagui in New South Wales, residents were advised to boil their water before utilising it for household tasks like brushing teeth, cleaning and cooking in the immediate aftermath of the fires.

In other areas like the Victorian towns of Buchan and Omeo, tap water was deemed unsafe for consumption altogether and residents were advised to only drink bottled water.

Experts also say that, moving forward, the loss of and damage of farmland and associated infrastructure will impact dairy, meat, wool and honey supplies. By early January, more than 50 dairy farms across southeastern Australia had been impacted by fire, restricting or ending their ability to produce. Many Australians also noticed increases in the cost of fresh produce at the supermarket during and after the bushfire crisis.

It wasn’t just communities directly affected by bushfires where the impact was felt - demonstrated by the hazardous bushfire smoke that blanketed cities including Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra for long periods as fires raged hundreds of kilometers away.

The smoke drifted across the Tasman to impact parts of New Zealand and, according to the World Meteorological Organisation, also made its way across the South Pacific Ocean to Argentina and Chile.

In January, Canberra measured the worst air quality index of any major city in the world, with people breathing air a staggering 22 times the hazardous rating. Melbourne’s air quality was also the worst in the world in mid-January, and the Australian Medical Association (AMA) warned that the length and density of smoke exposure was a new and possibly fatal health risk.

Pharmacies and hardware stores in smoke-impacted cities sold out of protective P2 masks and Australia’s busy summer events schedule was also affected. Victoria’s annual Falls Festival which draws more than 17,000 music fans to Lorne over New Years Eve was cancelled after it began, due to extreme weather conditions.

Horse races and cricket matches were also relocated, rescheduled or cancelled. The smoke also impacted qualifying matches for the Australian Open, with Slovenian tennis player Dalila Jakupovic forced to retire after a coughing fit on the outdoor courts in Melbourne and later telling the media “it’s not healthy for us, I thought we would not be playing today but we don’t have much choice.”

The impact of the toxic smoke was also felt in ambulance call-out numbers - with Ambulance Victoria reporting that on one particularly hazardous day, it received more than 160 requests for callouts compared to less than 90 on an average day.

Rebuilding Australia - both literally and metaphorically - will be a long journey.

On January 6, the Federal Government established the National Bushfire Recovery Agency to lead and coordinate the national response to rebuilding communities.

The agency is led by former Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police Andrew Colvin, and will administer a $2 billion National Bushfire Recovery Fund in the next two years.

A range of initiatives and supports are available to impacted communities including one-off disaster relief payments and 13 week allowances for eligible individuals, emergency relief delivered by the Salvation Army and St Vincent de Paul Society, payments for volunteer firefighters, concessional loans of up to $500,000 for affected small businesses and grants of up to $75,000 to primary producers to assist in responding to the impact of bushfires.

Additional funding is also being allocated for mental health services to support people to navigate the trauma commonly associated with natural disasters like bushfires. This funding includes mental health liaison officers facilitated by Beyond Blue to work with schools and early childhood services in bushfire impacted communities and access to 10 free mental health support sessions for affected individuals and families, as well as additional Medicare rebates for further sessions.

The Federal Government has also made an initial commitment of $50 million to support wildlife and habitat recovery. Funds will support on-ground wildlife rescue, protection and care services and increase the supply of seed and native plants. Up to $3 million will be provided to Taronga Zoo, Zoos Victoria and Zoos South Australia to treat injured wildlife and establish insurance populations of at-risk species.

Australian tourism, too, is suffering. The Australian Tourism Export Council estimates that the number of international tourists booking holidays to Australia is down by up to 20 per cent which will result in around $4.5 billion of revenue by the end of 2020.

In response, the Federal Government has allocated $76 million to a tourism recovery package including $25 million for a global marketing campaign and $10 million to support events, concerts, festivals and other attractions in bushfire-affected regions to encourage and promote regional tourism.

Community members have also started online campaigns, including Buy from the Bush and Spend With Them, to encourage people to support small businesses in impacted communities and help them regain lost income. In less than two months, Spend With Them has gained almost 200,000 followers on Instagram, providing a valuable platform to promote regional businesses.

Holidaying locally in bushfire-impacted communities throughout 2020 and beyond will also foster recovery efforts and aid small businesses.

Share this Article